The Strawberry Valley Project: A History

by Garn LeBaron Jr.

copyright © Garn LeBaron Jr., 2013, all rights reserved.

In his book Rivers of Empire, historian Donald Worster described early Mormon attempts at irrigating the Great Basin landscape of Utah. In a section titled, “The Lord’s Beavers,” he argued that although their early efforts were rather primitive, they were successful because they “did have a system of hierarchy and group discipline, and that critical quality made possible their rapid success in water manipulation.”1 Utah is a small state with a small population and small rivers, and Worster had bigger fish to fry in building his case that the Bureau of Reclamation became water carriers to an agribusiness empire. So he turned his attention to California, with its Imperial and Central Valleys, and only returned to look at Utah water insofar as it was used to further the empires of California.

However, the Mormons did not stop their irrigation efforts, and when they found the obstacles too large to overcome with their limited capital, they, like the Californians, also called upon the newly formed Bureau of Reclamation for assistance. Although the resulting edifices did not create hydraulic empires like those in California, thousands of small farms in Utah Valley flourished and the process of the land reclamation mirrored much more closely the ideas that had been originally envisioned in the Reclamation Act when it was passed in 1902. This then, is the story of the Strawberry Valley Reclamation Project, an early dam and reservoir project undertaken by the Bureau shortly after the passage of the Reclamation Act.

When the Mormons settled in the Salt Lake Valley in 1847, they first turned the waters of City Creek out of its bed and onto the parched floor of the Salt Lake Valley. This crude irrigation effort allowed them to grow enough crops to feed themselves during those early years of settlement. They soon expanded their settlements south into Utah Valley, and by 1851 had established Lehi, Alpine, American Fork, Pleasant Grove, Provo, Springville, Spanish Fork, Salem, and Payson. “This line of settlements utilized every mountain stream and was so spaced that the outlying farms and pasture lands of each community could touch the next and all the settlers could rally to meet external dangers or unusual internal challenges.”2 The first fifteen years of Mormon settlement in Utah Valley were marked by various levels of conflict with the local Ute Indians.3 Eventually, the US Government decided to remove the Utes, and in 1861 President Lincoln authorized the Secretary of the Interior to establish the Uintah Basin as a reservation for the Utes of the Territory of Utah.4 In 1865, a treaty was negotiated with the Utes where they gave up their claims to the land in Utah Valley and moved east across the Wasatch range and into the Uintah basin.5

The new settlers in the Utah Valley quickly appropriated the streams emerging from the Wasatch canyons and used them to irrigate their fields. These irrigation works were built cooperatively, with labor on the canal systems being exchanged for shares of water. Because the church encouraged cooperation and small farms, the irrigation systems in Utah largely avoided the speculative fever that accompanied other irrigation projects of the day.6 In 1895, farmers in Utah were irrigating over 400,000 acres of farmland, with an average farm size of 25 acres.7 92% of all farms were utilizing irrigation for watering crops.8

By the turn of the century, irrigation in Utah Valley had reached a plateau. All of the water from the spring runoff and from the permanently flowing streams in the valley had been appropriated, and many farmers had great difficulty with any crops later in the season. In his 1890 Agricultural Report, Newell noted,

There is more arable land than can be watered by the regulated flow of the rivers, and as a consequence, the area of tilled land has increased until limited by the amount of water available in ordinary seasons. In times of drought, therefore, the land more recently brought under cultivation cannot produce a crop, and considerable suffering exists among the later settlers . . . In times of drought, as during 1888 and 1889, the farmers having only third rights lost their crops and most of their trees and vines, except such as were watered by hand. Those holding secondary rights also lost heavily, and even among those having first or prior rights, the water was not sufficient for all demands.9

It was apparent to all, that if more water could be obtained, the farms would be more productive, and hence, more successful. For example, as early as 1889 the people of Springville and Mapleton had formed a committee and petitioned the governor “to ascertain if the waters of Strawberry Creek, in Strawberry Valley, and lying in the Indian Reservation, could be brought into Springville through Spanish Fork Canyon for irrigating purposes.”10

The Strawberry Valley is located directly to the east of the watershed drained by the Spanish Fork River. It is in Wasatch County, and was part of the Uintah Ute Indian reservation as established by President Lincoln in 1861 and approved by Congress in 1864. The Vernal Express described it as,

one entire stretch of meadow land, and is about 20 miles long by from 5 to 10 wide . . . Parties anticipating a pleasure trip could not do better than visit this glorious country . . . but by all means leave the firewater at home if any go, as Uncle Sam keeps the temptation from his wards and watches with a vigilant eye for anyone who would tempt the red man.11

With a base elevation of 7,500 feet, the valley is too cold for growing crops.12 The Ute Indian tribe leased it for grazing purposes, mainly to the Strawberry Valley Cattle Company.13 Records show that the tribe earned $13,000 in grazing lease income from the Strawberry Valley in 1900.14 Before the Strawberry Valley Project, the streams of the Strawberry Valley drained naturally from the mountainous regions in the north and west into the the Duchesne River, flowing southeast, and then into the Green River. The Strawberry River drainage is about 200 square miles, all above 7500 feet elevation and includes some of the highest parts of the Uinta mountain range.15

The head of the Bureau of Reclamation interpreted the Reclamation Act of 1902 as an authorization to create at least one reclamation project for each of the sixteen states covered under the act. It was also smart politically, because bringing Federal dollars to all the different states was a way to make all the states happy with the Bureau. Shortly after the act was passed, Mr. Newell, the head of the Bureau, met in Salt Lake City with Utah farmers to explain the act and its ramifications for the state of Utah.16 Under discussion at these initial meetings were plans to improve the Bear River and Bear Lake, damming and deepening of Utah Lake to improve irrigation for Salt Lake Valley, and a plan to divert the water from the Strawberry to reclaim “50,000 acres of arid land lying in the southern part of Utah county.”17 A third plan was to create a storage reservoir on the Weber River. The Utah Lake plan was tabled, and there were too many water rights conflicts involved to make the Bear and Weber plans feasible. This brought the Strawberry plan to the fore.18

There were three factors that, combined, created pressure to remove the Strawberry Valley from the hands of the Ute Indian Tribe. The first was the passage of the Newlands Reclamation Act along with the idea that the valley would make a good storage reservoir for the farms of southern Utah Valley. The second was the demand for allotments and the opening of the reservation to settlement. The third was the US Forest Service and their plans to establish forest reserves in Utah’s higher elevations.

As soon as the Dawes Act was passed opening the Oklahoma reservations up to settlement, there was agitation and speculation in Utah over when the Ute reservation would be opened to settlement. There was a widespread sentiment in Utah that the reservation was far too large for such a small group of people and that the land was just going to waste instead of being properly settled.19 The government made several attempts to convince the Utes to open their land up for allotments, but they unanimously refused. After the Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock decision in 1903,20 Congress now had the power to open the reservation without consent. Between 1898 and 1909, a series of different actions were taken to separate the Utes from their reservation lands, and “When the process was complete in 1909, the once four-million-acre reservation consisted of a patchwork of 360,000 acres with about a third of this amount designated as allotments.”21

The year of 1905 in particular was not a good one for the Ute Indian Tribe. On July 14, President Roosevelt issued two proclamations. The first removed over 1 million acres from the Uinta Indian Reservation and added it to the Uinta Forest Reserve.22 The second opened the Uinta Reservation lands to settlement.23 A third proclamation on August 324 and modified on August 14,25 set aside the lands needed for the Strawberry Reservoir, removing them from the reservation and assigning them to the Reclamation Service.26 Once the tribal lands of the Strawberry Valley were transferred to the Reclamation Service, the final obstacle to construction had been removed. The building of the storage reservoir and tunnel could now begin. What was initially a financial problem, later a political problem, had now become an engineering and construction problem to be managed by the Federal Government.

Between January and August of 1905, engineers drew the plans for the project and determined the feasibility. After the board of engineers declared the project feasible, the Strawberry Water Users Association was formed, with all members agreeing to pay $40/acre to cover the cost of the project.27 All of the lands within the project scope were subscribed almost immediately. As a condition for joining the water users association, users of prior rights on the Spanish Fork River had to agree to forfeit those rights, which were re-subscribed as new rights in the new water users association.28 Each holder of prior rights signed an individual contract with the Reclamation Service and the once the association was organized, the project was approved on December 15, 1905. $1.25 million was set aside from the reclamation fund to begin construction.

The Strawberry Valley project, as it was originally designed and constructed, consists of the following components:

On the south side of the reservoir (these are all collection structures that funnel water into the reservoir or retain water in the reservoir):

The Strawberry Dam, completed on October 29, 1912.

The dam spillway, completed on September 20, 1913.

The Indian Creek Dike, completed October 10, 1912.

Trail Hollow Intake Structure, completed September 30, 1912.

Trail Hollow Canal, completed November 5, 1912.

Indian Creek Crossing Diversion Dam and Intake Structure, completed November 5, 1912.

Indian Creek Canal and bridges, completed September 20, 1912.

Indian Creek Terminal Chute and Weir, completed September 20, 1912.

On the west side of the reservoir:

The Strawberry Tunnel East Portal diverts water from the reservoir into the Great Basin.

On the west side of the tunnel:

The Strawberry Tunnel West Portal, tunnel completed June 20, 1912.

The Diamond Fork construction road and bridges, completed in 1907.

The Spanish Fork Diversion Dam, completed December 13, 1908.

The Spanish Fork Power Canal, completed December 13, 1908.

The Spanish Fork Diversion Structure and Powerhouse, completed December 13, 1908.

Running Southwest from the Spanish Fork Power Canal:

The High Line Canal and Laterals 20 and 30, completed December 1, 1916.

High Line Canal Laterals 31, 32, and 34, completed June 1917.

Running Northwest from the Spanish Fork Power Canal:

The Springville-Mapleton Lateral, completed October 1918.

Water is collected in the reservoir naturally from Strawberry Creek and its tributaries on the North. Additional water is collected from Indian Creek and Trail Hollow Creek with the canal and diversion structures on the south side of the reservoir. As built, the reservoir had a storage capacity of 278,000 acre feet and covered 8,200 acres. Storage water from the reservoir is drawn through the tunnel to the west and into the Diamond Fork of the Spanish Fork River. At the base of Spanish Fork Canyon, the diversion dam diverts some water directly into the 3.3 mile power canal. Water from the main stem of the river continues into the valley to irrigate the central part of the project. At the end of the power canal, another diversion structure diverts some water into the High Line canal, and the remainder into the penstock for the powerhouse. Water from the High Line canal irrigates the south side of the project. Water from the powerhouse is returned to the river and irrigates the central part of the project. The Springville-Mapleton Lateral draws water from the power canal at an upstream location to irrigate the north side of the project.29

On March 6, 1906, the Reclamation began road construction, work camp construction, and preliminary work at both the east and west tunnel portals. During the summer and fall of 1906, the 30 mile wagon road serving both tunnel portals was built. A work camp was constructed and tunnel boring work was started using electric drills driven by gasoline powered generators. Due to slow progress, work on the tunnel was stopped in July of 1907 after 1,565 feet of tunnel had been excavated.30

In December of 1908, the powerhouse was completed and the electrical generators were installed. Transmission lines were run from the generating plant to the tunnel. This allowed for the installation of air compressors at each portal. The remainder of the tunnel was bored using 3 1/4 inch Sullivan Rock Drills and the work proceeded much faster with the new technology.31

There were several problems with tunnel construction. At first, the electric drills were much too slow. Once the air drills were installed, the workers encountered a great deal of water in the tunnel, running from 7 to 9 second-feet for the remainder of the project.32 This made for miserable working conditions, but there was nothing to be done other than finish the job.33 Once the tunnel boring was completed in June of 1912, the entire structure was lined with concrete. Water was released from the reservoir into the tunnel for the first time on September 13, 1913.34

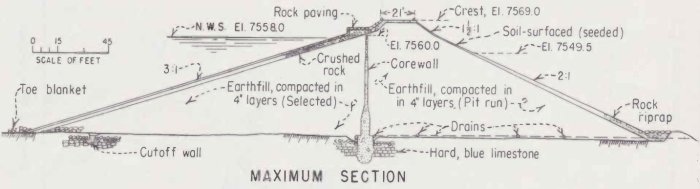

Construction on the dam and the Indian Creek Dike proceeded simultaneously with the construction of the tunnel. The dam was a straightforward earthen fill embankment structure with a solid concrete corewall providing structural strength. At 60 feet high and only 485 feet long, it is not nearly as impressive as many of the structures that the Bureau was to build later in the 20th century.35

Once the tunnel was completed, there was water ready for irrigation. This led to a dispute between the members of the association who were subscribed to the High Line Canal and those who were subscribed to the existing irrigation works extending from the Spanish Fork River. The river users saw that water was available immediately, and their problems were solved. They saw no reason to participate in the construction and associated costs of building the High Line canal.36 The result of this dispute caused the Secretary of the Interior to abrogate the contract with the water users association, and new contracts had to be negotiated on new terms. This was a time consuming and costly process that ultimately led to a reconfiguration of the project. Under the new terms, water was sold at different rates to users depending on which canal system they were using. Spanish Fork canal users did not have to pay the same rates as High Line and Springville-Mapleton canal users.37

Once the tunnel was complete, the work camps and the power lines were removed from the portals. The powerhouse became a generating station for the towns located around the project. Spanish Fork, Salem, Payson, and Springville drew electricity from the powerhouse for municipal use. Sales of electricity also helped to defray the costs of the project.38

The lands surrounding the Strawberry Reservoir as part of the project were leased by the government for grazing. The government ultimately paid the Ute Indian agency $1.25/acre for the 56,868 acres surrounding the reservoir. Five payments of $14,217.13 were paid between 1912 and 1917.39 In the early years of the project, the rates were lower.40 In the later years of the project the rates were higher. Ultimately, the lands were leased by the High Line Canal Company for the benefit of the membership.41

Construction of the High Line canal began in 1915. It was a 17.5 mile long canal that delivered 300 second-feet of water. Laterals branching off the canal ultimately delivered water to over 22,000 acres of farmland. Almost all of the laterals were concrete lined in order to prevent seepage.42

The Springville-Mapleton canal did not start construction until 1917. The government initially had difficulty finding subscribers for this canal because of the additional costs that were incurred by the need to build a concrete siphon across the Spanish Fork River. The water from the canal was ultimately subscribed at $50-$60 per acre-foot of water43 and when construction was completed in 1918, the canal delivered 85 second-feet of water to approximately 10,000 acres of land.44

By 1921 the project was mostly complete. Over 270,000 acre feet of water were being stored in the reservoir and over 50,000 acre feet of water were being delivered every summer to over 59,000 acres of farmland on the project.45 The total construction cost of the project was $3.5 million spent over the course of fifteen years.46 The southern end of Utah Valley prospered, and many new homes and businesses grew in the wake of the project. The farms on the project grew a variety of crops including alfalfa, hay, silage, cereal crops and grains, and a wide variety of fruits and vegetables including apples, cherries, peaches, apricots, pears, grapes, tomatoes, potatoes, corn, beans, and melons. It was the cash crop of sugar beets that really drove the profits of the project. Three different sugar beet factories arose in the valley.47 The farmers would plant the beets in the spring, and they were tended throughout the summer. Once the beets were dug and harvested, they would be sold to the factories where they were processed into sugar. The waste product from the sugar production process made good animal feed and most farmers would use this as supplemental feed for their stock in the winter.48

So, sugar. And some livestock feed, fruits, and vegetables. There is no question that the project provided a great benefit to the 2400 farms49 watered by the Strawberry. Crop yields improved and the farms were generally prosperous. People were not becoming fabulously wealthy, but a decent living could be made and a family could be provided for on one of these farms.50 Alexander made the argument that, “on the basis of the evidence, it is difficult to conclude that the Strawberry Valley Project has been anything but successful.”51 But the water for these farms was expensive, ranging from $45 to $65 per acre-foot. By the standards of the Bureau of Reclamation, the Strawberry was a small project, but one that required extensive engineering and the expenses associated with such engineering. The main tunnel alone was almost 1/3 of the project cost.

And so we return once again to the beginning, right after the Reclamation Act was passed. The Bureau was investigating potential water projects for the State of Utah. In their second annual report they reported extensively on the potential of the Utah Lake project, where the lake could be made deeper, the outlet channel could be lowered, and improvements could be made to the Jordan River and some existing canals near the Jordan.52 The same report also analyzed the potential of the Bear River and the Bear Lake, with an opportunity for irrigating almost 300,000 acres with a much simpler design and a much lower project cost than the Strawberry.53 All of the early newspaper articles about the Reclamation Service in Utah reported breathlessly on the possibilities of the Utah Lake and Bear Lake projects.54

Then, in 1905 came this interesting article in the Salt Lake Tribune stating in part,

It was the opinion of every practical irrigator, . . . that the Utah Lake project was the first in importance and in merit; then came the Bear Lake project; then the Weber River project; then the Sevier River project, with Strawberry nowhere. And now Strawberry is first, with the prospect that the Weber River project will be the second and the others nowhere. It is a curious commentary on the difference between the popular judgment and the results of actual scientific examination.55

So what transpired to bring the smaller and more difficult Strawberry Project to the fore? The first clue comes from Professor Swendsen in the Fourth Annual Reclamation report where he states,

By the end of the field season of 1904 the Utah Lake and Bear Lake projects were very thoroughly understood so far as engineering problems were concerned, and these results, together with the review of water-right matters and other complicating elements, led to the conclusion that neither could be put under construction for some years to come . . . The consideration of Weber River, another of the large and valuable water resources of the State, was barely begun when conflicting interests indicated the advisability of discontinuing the work there. The Strawberry Valley had proved on examination to be the most feasible and least complicated of all projects so far considered . . .56

Water rights were at issue. People had been irrigating and negotiating over the waters of the Wasatch Front since 1847. Things were contentious. Here was a new agency that needs to look good. It needed a project in Utah, but it could only see litigation as the future of the most feasible projects. The final clue comes from the 1905 irrigation hearings in the House of Representatives where director Newell states,

In every part of the arid region of the United States certain land and water rights have already been acquired, which, if not relinquished, prohibit the construction of reclamation works. Excepting in the cases of Indian reservations which may be opened, and in which is a free field, practically every irrigable project has been examined or filed upon in part by some individual or corporation. These may be operating under the Carey Act for example, or under some State law or right of way granted by the Secretary of the Interior. Thus work must be done with great care and patience to secure a release from these conditions.57

It becomes clear now that the Strawberry Valley Project was chosen for the first Bureau project in Utah because it was the most politically expedient. The Strawberry Valley, as part of the Uintah reservation, was about to be opened up to allotments. All the Reclamation Service had to do was convince the government to move that valley over to their side of the ledger. Yes, the Indians had the rights to that water, but they had no one to advocate for them. It was easy to take those rights, much easier to build a complicated small project than to spend the time litigating the water rights for any of the other larger ones. The Bureau eventually paid the Tribal Indian Agency for the land of the Strawberry Valley, but no one ever paid the Ute Indians for the water.

A note on the drawings and photographs in this paper. All the photographs are from the Historic American Engineering Archive at the Library of Congress. The entire photo set is located here: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/ut/ut0100/ut0177/data and here: http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/ut/ut0100/ut0177/photos/.

The US Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division has a “Built in America” Collection located at:

http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/habs_haer/

The Rights for Reproductions for these government items are here:

http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/habs_haer/hhres.html

All of the drawings, including the project map below were cropped from a single document titled “Strawberry Valley Project: Utah, Utah and Wasatch Counties.” This document is stored in the Western Waters Digital Library as part of the BYU Harold B. Lee Library Digital Collections and is located here: http://cdm15999.contentdm.oclc.org/cdm/ref/collection/WesternWatersProject/id/667

Strawberry Valley Project Map

Notes

1 Donald Worster, Rivers of Empire, (New York: Pantheon Books, 1985), p. 77

2 Richard Douglas Poll, Thomas G. Alexander, Eugene E. Campbell, and David E. Miller, Utah’s History, (Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1989), p. 139.

3 For an excellent description of the difficult relationship between the early Mormon settlers of Utah Valley and the Utah Lake Nuche, see Jared Farmer, On Zion’s Mount: Mormons, Indians, and the American Landscape, (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008), pp. 62-104

4 Charles J. Kappler, ed., Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Vol 1, Laws, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904), http://digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/Vol1/HTML_files/UTA0899.html (accessed April 28, 2013), p. 900.

5 Farmer, On Zion’s Mount, pp. 101-104.

6 Charles Hillman Brough, Irrigation in Utah, (Baltimore, MD: The John Hopkins Press, 1898), pp. 5-13.

7 Brough, Irrigation in Utah, p. 75.

8 F. H. Newell, Report on Agriculture by Irrigation in the Western Part of the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894), p. 2.

9 Newell, Report on Agriculture by Irrigation, p. 232.

10 John Tuckett, “Relative to Irrigation,” Deseret News, July, 6, 1889. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den1895/id/47492/rec/158 (accessed February 7, 2013).

11 “Strawberry Valley,” Vernal Express, September 1, 1892. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/vernal1/id/5406/rec/37 (accessed February 7 2013).

12 “State Land Board,” Deseret News, November 14, 1896, http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/deseretnews5/id/15246/show/15357/rec/7 (accessed February 7, 2013).

13 Strawberry Valley Cattle Co. vs. Chipman, 13 Utah, 454 (Supreme Court of Utah, June 3, 1896), Pacific Reporter Vol. 45, (St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co., 1896) pp. 348-352. The court held that the tribe did indeed own the Strawberry Valley by the fact that they had given up claims to all other lands in exchange for their reservation, of which the valley was a part. The court also held that the lease was valid and that Chipman had to pay damages for trespass on the lease. This ruling came after the cattle company had filed multiple lawsuits against various trespassers in an attempt to keep them off the lease. “Uintah Grazing Lease,” Salt Lake Tribune, March 17, 1895, http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/slt15/id/21842/rec/76 (accessed February 7, 2013). “Lease Case Affirmed,” Salt Lake Tribune, June 4, 1896, http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/slt16/id/37080/rec/150 (accessed February 7, 2013).

14 Oscar H. Lipps, “The Indians of Utah.” Salt Lake Tribune, January 1, 1900. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/sltrib21/id/35373/rec/1 (accessed February 7, 2013).

15 George L. Swendsen, “Operations in Utah,” Fourth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1904-1905, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1906), p. 332.

16 “Reclamation of the Arid West.” Deseret News, October 1, 1902. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den3/id/4511/rec/102 (accessed February 7, 2013). Also, “Water Problem Being Considered.” Deseret News, October 2, 1902. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den3/id/4678/rec/103 (accessed February 7, 2013).

17 “Probe Water Problem.” Salt Lake Tribune, October 03, 1902. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/sltrib22/id/33237/rec/197 (accessed February 7, 2013).

18 George L. Swendsen, Fourth Annual Report, pp. 329-331.

19 William T. Smith, “Historical Account of the Utes in Utah,” Salt Lake Tribune, January 1, 1902. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/sltrib22/id/69248/rec/1 (accessed February 7, 2013).

20 Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, 187 U.S. 553 (1903), In Justia.com, http://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/187/553/ (accessed April 19, 2013).

21 Virginia McConnell Simmons, The Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico, (Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado, 2000), p. 225

22 Proclamation 7-14-1905, http://www.theodore-roosevelt.com/images/research/trproclamations/580.pdf (accessed April 30, 2013).

23 Proclamation 7-14-1905, http://www.theodore-roosevelt.com/images/research/trproclamations/581.pdf (accessed April 30, 2013).

24 Proclamation 8-3-1905, http://www.theodore-roosevelt.com/images/research/trproclamations/589.pdf (accessed April 30, 2013).

25 Proclamation 8-14-1905, http://www.theodore-roosevelt.com/images/research/trproclamations/591.pdf (accessed April 30, 2013).

26 For a thorough discussion of how the lands were taken from the Ute Indians, see Kathryn L. Mackay, “The Strawberry Valley Reclamation Project and the Opening of the Uintah Indian Reservation,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 50:1 (Winter 1982), pp. 82-89.

27 “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Ninth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1909-1910, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1911), p. 268.

28 Swendsen, Fourth Annual Report, pp. 333-334.

29 “Strawberry Valley Project: Photographs, Written Historical and Descriptive Data,” Historic American Engineering Record, UT-26, pp. 1-3. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/ut/ut0100/ut0177/data/ut0177data.pdf (accessed February 7, 2013).

30 Ninth Annual Report, pp. 268-269.

31 Ninth Annual Report, pp. 270-271.

32 J. L. Lytel, “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Thirteenth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1913-1914, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1914), p. 395

33 “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Eleventh Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1911-1912, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1912), p. 173.

34 Lytel, Thirteenth Annual Report, p. 393, 395.

35 Eleventh Annual Report, p. 170.

36 “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Twelfth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1912-1913, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1914), p. 216.

37 Lytel, Thirteenth Annual Report, pp. 395-398.

38 Lytel, Thirteenth Annual Report, p. 394.

39 Eleventh Annual Report, p. 252.

40 J. L. Lytel, “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Fourteenth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1914-1915, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1915), p. 276.

41 W. L. Whittemore, “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Twentieth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1920-1921, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1921), pp. 328-329.

42 Lytel, Fourteenth Annual Report, p. 267, J. L. Lytel, “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Seventeenth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1917-1918, (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1918), p. 310.

43 Lytel, Seventeenth Annual Report, p. 286, Wittemore, Twentieth Annual Report, p. 328.

44 Lytel, Seventeenth Annual Report, p. 310.

45 Whittemore, Twentieth Annual Report, p. 322.

46 Whittemore, Twentieth Annual Report, p. 334.

47 Whittemore, Twentieth Annual Report, p. 331.

48 “Strawberry Valley Project: Photographs, Written Historical and Descriptive Data,” Historic American Engineering Record, UT-26, pp. 77-78. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/ut/ut0100/ut0177/data/ut0177data.pdf (accessed February 7, 2013).

49 Whittemore, Twentieth Annual Report, p. 332.

50 For an in depth discussion of crop yields and profitability of farming on the Strawberry Project, see “Strawberry Valley Project: Photographs, Written Historical and Descriptive Data,” Historic American Engineering Record, UT-26, pp. 79-98. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/ut/ut0100/ut0177/data/ut0177data.pdf (accessed February 7, 2013).

51 Thomas G. Alexander, “An Investment In Progress: Utah’s First Federal Reclamation Project, The Strawberry Valley Project,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 39:3 (Summer 1971): 304.

52 George L. Swendsen, “Investigations in Utah,” Second Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1902-1903, (Washinton, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904), pp. 459-470

53 Swendsen, Second Annual Report, pp. 480-486.

54 “Talk With Mr. Newell,” Deseret News, October 1, 1902, http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den3/id/4511/rec/102 (accessed February 7, 2013). “Water Problem Being Considered,” Deseret News, October 2, 1902, http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den3/id/4678/rec/103 (accessed February 7, 2013). “Reclamation of Arid Lands,” Deseret News, August 24, 1903, http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den7/id/65564/rec/202 (accessed February 7, 2013). “Progress of the Reclamation Service In Utah,” Deseret News, December 17, 1904, http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den8/id/74149/rec/301 (accessed February 7, 2013).

55 “The Strawberry Valley Project,” The Salt Lake Tribune, May 13, 1905.

56 Swendsen, Fourth Annual Report, p. 329.

57 House Committee on Irrigation of Arid Lands, Relating to Projects for the Irrigation of Arid Lands Under the National Irrigation Act and the Work of the Division of Irrigation Investigations of the Agricultural Department in Connection With Irrigation of Arid Lands, 58th Cong., 2d sess., 1905, H. Hrg. 381, 17-18.

Works Cited

Alexander, Thomas G. “An Investment In Progress: Utah’s First Federal Reclamation Project, The Strawberry Valley Project,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 39:3 (Summer 1971), pp. 286-304.

Almanac of Theodore Roosevelt. “The Complete Presidential Proclamations by Theodore Roosevelt.” http://www.theodore-roosevelt.com/trproclamations.html (accessed April 30, 2013).

Brough, Charles Hillman. Irrigation In Utah. Baltimore, Maryland: The John Hopkins Press, 1898.

Farmer, Jared. On Zion’s Mount: Mormons, Indians, and the American Landscape. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

Kappler, Charles J., ed. Indian Affairs: Laws and Treaties, Vol 1, Laws. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/Kappler/Vol1/HTML_files/UTA0899.html (accessed April 28, 2013).

“KAPPLER’S INDIAN AFFAIRS: LAWS AND TREATIES.” Oklahoma State University – Library – Home. http://digital.library.okstate.edu/kappler/index.htm (accessed April 20, 2013).

“Lease Case Affirmed.” Salt Lake Tribune, June 4, 1896. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/slt16/id/37080/rec/150 (accessed February 7, 2013).

Lipps, Oscar H. “The Indians of Utah.” Salt Lake Tribune, January 1, 1900. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/sltrib21/id/35373/rec/1 (accessed February 7, 2013).

Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock. 187 U.S. 553 (1903). In Justia.com,

http://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/187/553/ (accessed April 19, 2013).

Lytel, J. L. “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Thirteenth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1913-1914. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1914. pp. 393-404.

Lytel, J. L. “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Fourteenth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1914-1915. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1915. pp. 265-278.

Lytel, J. L. “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Fifteenth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1915-1916. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1916. pp. 400-426.

Lytel, J. L. “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Sixteenth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1916-1917. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1917. pp. 280-325.

Lytel, J. L. “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Seventeenth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1917-1918. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1918. pp. 309-325.

Mackay, Kathryn L. “The Strawberry Valley Reclamation Project and the Opening of the Uintah Indian Reservation,” Utah Historical Quarterly, 50:1 (Winter 1982), pp. 68-89.

Newell, F. H. Report on Agriculture by Irrigation in the Western Part of the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1894.

Poll, Richard Douglas, Thomas G. Alexander, Eugene E. Campbell, and David E. Miller. Utah’s History. Logan, Utah: Utah State University Press, 1989.

“Probe Water Problem.” Salt Lake Tribune, October 03, 1902. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/sltrib22/id/33237/rec/197 (accessed February 7, 2013).

“Progress of the Reclamation Service in Utah.” Deseret News, December 17, 1904. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den8/id/74149/rec/301 (accessed February 7, 2013).

“Reclamation of Arid Lands.” Deseret News, August 24, 1903. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den7/id/65564/rec/202 (accessed February 7, 2013).

“Reclamation of the Arid West.” Deseret News, October 1, 1902. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den3/id/4511/rec/102 (accessed February 7, 2013).

Simmons, Virginia McConnell. The Ute Indians of Utah, Colorado, and New Mexico. Boulder, Colorado: University Press of Colorado, 2000.

Smith, William T. “Historical Account of the Utes in Utah.” Salt Lake Tribune, January 1, 1902. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/sltrib22/id/69248/rec/1 (accessed February 7, 2013).

“State Land Board.” Deseret News, November 14, 1896. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/deseretnews5/id/15246/show/15357/rec/7 (accessed February 7, 2013).

“Strawberry Valley.” Vernal Express, September 1, 1892. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/vernal1/id/5406/rec/37 (accessed February 7, 2013).

Strawberry Valley Cattle Co. vs. Chipman. 13 Utah, 454 (Supreme Court of Utah, June 3, 1896). Pacific Reporter Vol. 45. St. Paul, Minnesota: West Publishing Co., 1896. pp. 348-352.

“Strawberry Valley Project: Photographs, Written Historical and Descriptive Data,” Historic American Engineering Record, UT-26. http://lcweb2.loc.gov/pnp/habshaer/ut/ut0100/ut0177/data/ut0177data.pdf (accessed February 7, 2013).

Swendsen, George L. “Investigations in Utah,” Second Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1902-1903. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1904. pp. 451-486.

Swendsen, George L. “Operations in Utah,” Fourth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1904-1905. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1906. pp. 329-334.

“Talk with Mr. Newell.” Deseret News, October 1, 1902. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den3/id/4511/rec/102 (accessed February 7, 2013).

“The Strawberry Valley Project.” Salt Lake Tribune, May 13, 1905. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/sltrib23/id/107876/rec/132 (accessed February 7 2013).

Tuckett, John. “Relative to Irrigation.” Deseret News, July 6, 1889. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den1895/id/47492/rec/158 (accessed February 7, 2013).

“Uintah Grazing Lease.” Salt Lake Tribune, March 17, 1895. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/slt15/id/21842/rec/76 (accessed February 7, 2013).

U.S. Congress. House. Committee on Irrigation of Arid Lands. Relating to Projects for the Irrigation of Arid Lands Under the National Irrigation Act and the Work of the Division of Irrigation Investigations of the Agricultural Department in Connection With Irrigation of Arid Lands. 58th Cong., 3rd sess., March 2, 1905., H. Hrg. 381.

“Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Ninth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1909-1910. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1911. pp. 267-278.

“Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Eleventh Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1911-1912. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1912. pp. 170-174, 252.

“Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Twelfth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1912-1913. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1914. pp. 212-219.

“Water Problem Being Considered.” Deseret News, October 2, 1902. http://udn.lib.utah.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/den3/id/4678/rec/103 (accessed February 7, 2013).

Whittemore, W. L. “Utah, Strawberry Valley Project,” Twentieth Annual Report of the Reclamation Service: 1920-1921. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1921. pp. 322-335.

Worster, Donald. Rivers of Empire. New York: Pantheon Books, 1985.

My grandfather John Mitchell Cowan with his partner Jed Lovelace were given 5+ miles of the Strawberry High Line Canal from Payson Utah to Santiquin. Jed Lovelace was killed by an untrained young horse rearing its head, and broke Jed’s neck. The whole project was put upon my grandfather, and my father Glenn Fay Cowan his son. they worked around 1915 putting concrete down and did everything by horses. My father wrote about it and I have possession of a picture that was on a post card of the Cowan Construction team digging their portion. My grandfather was born in 1862, and my father was born in 1895. Dad didn’t marry until 1941. I was born on my grandparents 55th wedding anniversary in Payson, Utah.

Mary Barbara Cowan Buxton

June 30, 2019 at 7:38 pm

Great article. First time I heard of the Lone wolf decision in footnote 20.

Martin Morgan

November 24, 2020 at 9:12 am